It's hard to think of two activities that I am less interested in than football and gambling.

When it comes to the pigskin, my dad wasn't into it, so I wasn't exposed to football culture until I was older. That's when I realized most people are obsessed with football, and I was weird for not being among them. In general, I subscribe to the Noam Chomsky School of Understanding Professional Sports, which is to say I agree with his assessment that it’s a form of population control that, “keeps [people] from worrying about things that matter to their lives that they might have some idea of doing something about.”

As for gambling, I understand the baseline appeal, but it's just not the type of reward system that gets me going. The few times I tried my hand, I felt nervous, and when I eventually lost, I thought, "That's it?" Clearly, it's just not for me.

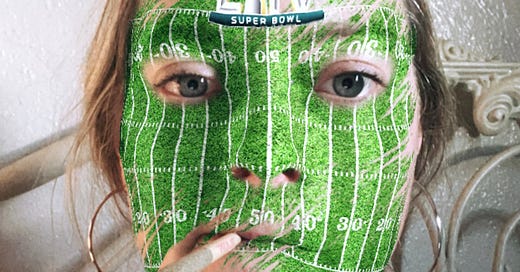

That said, I'm also not a fan of the Super Bowl, considering it combines two of my least favorite activities. While I actively avoid watching it, though, I've found that it works its way into my consciousness every year, probably because I work in media. When thinking about the Super Bowl, my thoughts always turn to vices. The event is a display case for them, and the advertising machine actively underwrites this.

I don't believe in the concept of vice as it's commonly understood. Merriam-Webster defines the term as:

moral depravity or corruption: wickedness

a moral fault or failing

a habitual and usually trivial defect or shortcoming

Legally speaking, law enforcement tends to use the word "vice" as an umbrella for crimes—like those involving drugs, gambling, prostitution, et cetera—that society considers inherently immoral.

How could an act be inherently immoral? It can't. Our folly as humans is to blame where it is not deserved to get ourselves off the hook—we criminalize and stigmatize behaviors rather than address the underlying issues that cause them in the first place. For some, it's easier to sweep it under the rug rather than recognizing the compulsion to engage in certain behaviors as natural, fully human, and worthy of addressing according to context.

On the most basic level, I look to the Catholic Church for guidance regarding my understanding of vice (to quote fellow Huntington, NY native Walt Whitman, "I contain multitudes").

In 1274, St. Thomas Aquinas wrote in Aquinas Ethicus: The Moral Teaching of St. Thomas, Vol. 1, "Human law is laid down for a multitude, the majority of whom consists of men not perfect in virtue. And therefore not all the vices from which the virtuous abstain are prohibited by human law, but only those graver excesses from which it is possible for the majority of the multitude to abstain, and especially those excesses which are to the hurt of other men, without the prohibition of which human society could not be maintained, as murder, theft, and the like."

Basically, St. Thomas Aquinas was smart enough to distinguish between things that are potentially personally harmful and should be left to the individual versus those that actively hurt other people, like murder and theft, and therefore must be monitored by the state. Beyond that, I depart from the Catholic Church in what qualifies as a vice (obviously), but I maintain that some of my childhood religion's earlier thinkers were on the right path.

So, how does this relate to the Super Bowl? The event is a veritable vice parade. Because of religion and other moralizing elements of society, many people tend to associate vice with criminality. Another way to look at so-called "vices" is to see where they intersect with entertainment, instead, since many of us are indulging in such activities for just that purpose.

Through its advertising apparatus, the Super Bowl celebrates various activities that have entertainment and therapeutic value and the potential for abuse if indulged in too thoroughly: alcohol, food, sex, sports, pharmaceuticals, and gambling are a handful of examples.

Weed isn't included. Thanks to an entanglement of state and federal laws, none of which explicitly ban cannabis advertising, it's legally risky for an entity to run weed ads, so it's become de facto impossible to do so.

The official reason is that cannabis is still Schedule I and, therefore, federally illegal. Alcohol is alcohol—we, as a society, decided that it's a morally justifiable and state-sanctioned substance a long time ago. I could talk about that hypocrisy for days, but I think it's worth examining other vices that beg the question that has become the driving force behind my entire career: why are some "vices" okay and others aren't?

Legal betting has enjoyed a much wider audience since the Supreme Court struck down a federal ban in 2018, which led to a surge in advertising during sporting events since then. Gambling and the advertising revenue produced by it essentially keeps professional sports in business, especially during COVID.

It's not like gambling is legal everywhere—both gambling and weed were mostly illegal just a handful of years ago and have soared in accessibility in different states since then. But companies like DraftKings, Fan Duel, Bet MGM, and others have free reign to display their wares on national television. At the same time, cannabis remains a pariah, despite the industry's near-desperate willingness to toss money into the advertising machine.

The first cannabis company to attempt to place a national advertising spot was MSO Acerage Holdings, of which John Boehner is a board member (speaking of hypocrisy). They tried for the Super Bowl in 2019, when it would have appeared alongside brands like Michelob, PepsiCo, Amazon, Anheuser-Busch InBev, Burger King, and Procter & Gamble, among many others.

CBS rejected it, telling the company that the ad was "not consistent with the network's advertising policies." CBS told Vox that they do "not currently accept cannabis-related advertising."

Interestingly, the ad was supposed to be a PSA about the benefits of medical cannabis. None of the company's products were promoted. The hypocrisy goes far beyond so-called vices—the medicinal benefits of cannabis are somehow still threatening. Yet, ads for pharmaceuticals, which come from a behemoth of an industry that directly exploits society's ills, are largely overlooked.

Honestly, sometimes it feels personal. If I have to watch commercial after commercial hearing about erections and side effects that include anal leakage and brain hemorrhages, knowing that money comes from legal sales of pills that have hurt and killed people I love, then everyone else can deal with a weed spot about helping cancer patients or treating chronic pain.

I guess I just don't get it. Money is the answer to why anything does or does not happen, but in this case, it's not so clear-cut. Liability is also an insurmountable issue at present, but even that is bullshit. Gambling, despite not being fully legal everywhere, is getting more of a free pass because it is literally made up of money—it's not hard to see why the restrictions around it are loosening, particularly in professional sports during an era where in-person fan participation and, therefore, ticket sales, is verboten.

But cannabis, as an industry, has plenty of money, too, especially at the top. Even the NFL has chilled out on it a little bit, no longer suspending players for testing positive for THC. So why can't they be allowed to join in the capitalist fun? My guess is the same as it always is: good old-fashioned reefer madness.

Recently published

For Forbes I wrote about Luke Scarmazzo, a cannabis prisoner who was approved by Trump’s administration to be pardoned, only to have it denied at the 11th hour after he and his family had already been notified that he would be coming home. This happened the night before Biden’s inauguration and, per tradition, no reason was given. I spent the last couple of weeks talking to Luke, who is still imprisoned with 10 years to go on his sentence , as well as others involved in his case to find out what happened.

I have a brand new column! It’s about marketing and branding in the cannabis industry and it’s called “On Brand.” It runs at WeedWeek and is sponsored by Mattio Communications:

Column 1 talks about marketing to the “canna-curious”

Column 2 talks about the industry’s push to market dabs to mainstream customers

For the San Diego Union-Tribune/Pacific I wrote about Mike Shelbo, a San Diego County local who appears on season 2 of Netflix’s “Blown Away”

My latest Cannabitch podcast features legendary Humboldt County grower Johnny Casali—we talk his mom’s strain genetics, his incarceration, the CAMP years, and his path back into legal weed and what’s next for his legal grow, Huckleberry Hills Farm

Thanks for being here! Have a…great Super Bowl weekend!